Ñuu Dzavui

In Mixtecarte we have roots of the Mixteco people, who recognize themselves as “Ñuu Dzavui” “The people of the rain”, and speak the “Dza’a Dzavui” that is to say, “The language of the Rain”, in some of its current variants. The history of the “Pueblo de la Lluvia” lives on in pre-Hispanic codices such as the Nuttal, Vindobonensis, Selden, and works such as “Origen de los Indios del Nuevo Mundo e Indias Occidentales” by Dominican Friar Gregorio García, “Historia de Oaxaca” by José Antonio Gay, “Reyes y Reinos de la Mixteca” by Alfonso Caso, among many other works.

But whatis Plumary Art?

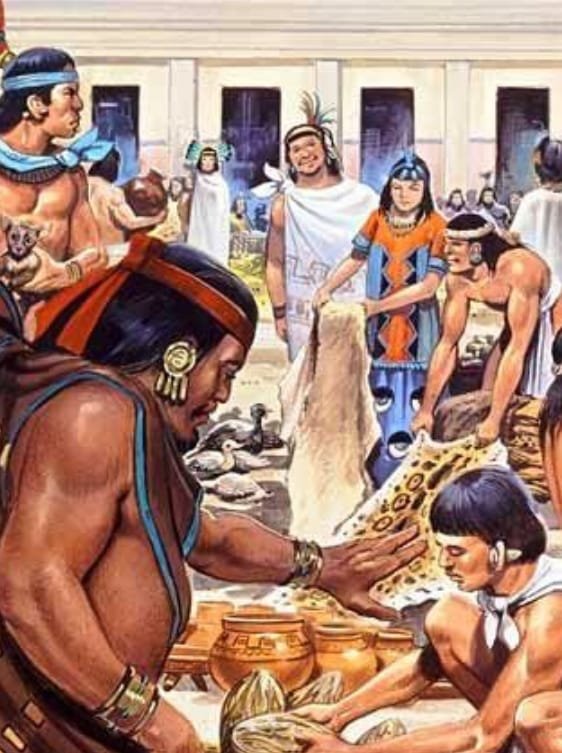

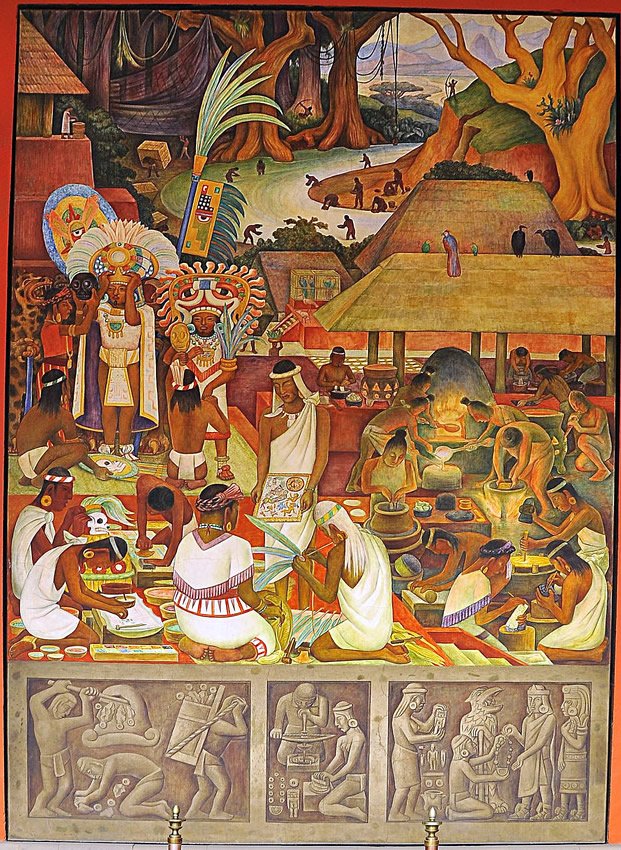

Plumary art has been present in Mexico since time immemorial, and in essence is the use of feathers naturally shed by birds to make flags, shields, pictographic compositions, clothing, symbols of power/authority, ornaments, etc. The best feathers and feather works were reserved for the noble class, rulers, and distinguished warriors, but they were also available in famous markets of the time such as Yodzo Coo (Coixtlahuaca, Oax.) or Tlatelolco, in Mexico City.

Huisi Tnumi/Arte Plumario/Amantecayotl

According to the great work of Fray Francisco de Alvarado “Voces del Dzaha Dzavui” from the year 1593, Arte Plumario is called “Huisi Tnumi”, where the word “Huisi” designates an art or trade, and the word “Tnumi” is the name for small feathers. “Tay” means man and “Ña’a” means woman. Therefore, “Tay Huisi Tnumi” means “Feather Artist” (man), while “Ña’a Huisi Tnumi” means “Feather Artist”, referring to the woman

. On the other hand, in the Nahuatl-speaking world, the word “Amantecayotl” has been used to designate the feather art. This is because in the times of Tenochtitlan, the people who dedicated themselves to this art came from the neighborhood of “Amanalco” which means “Near the Water” and whose gentilicio is “Amantecatl”, regardless of the sex of the performer.

Plumary Art Ñuu Dzavui/Mixteco through time

Ancient times

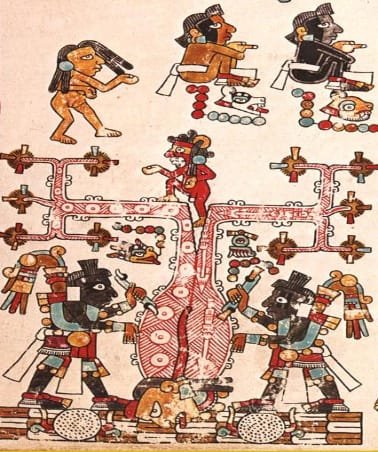

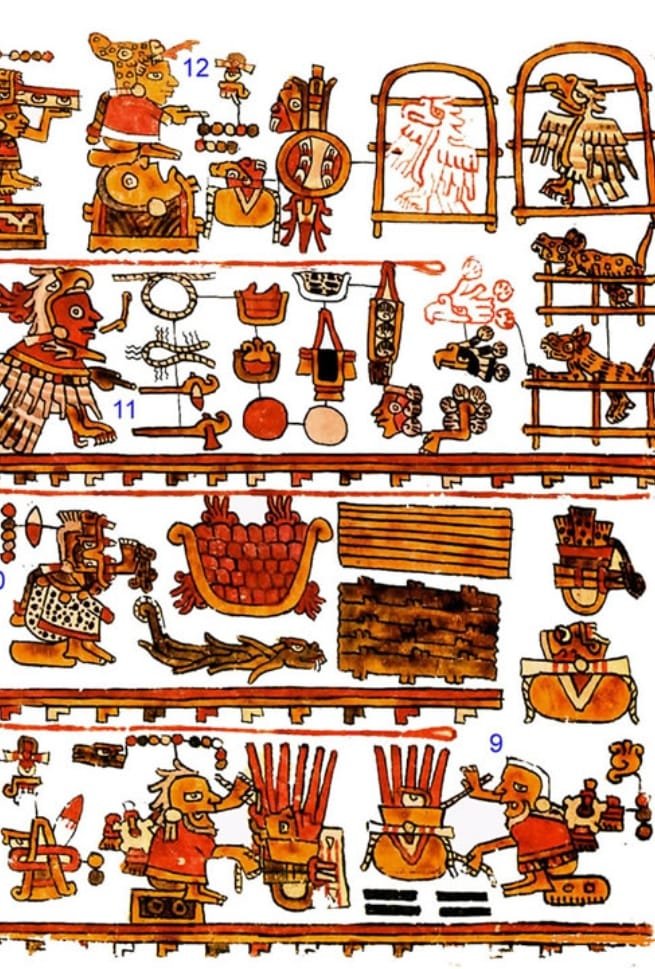

In the ancient times of the “Town of Rain”, it was already customary to keep birds in aviaries to obtain their feathers through the natural molting process. In plate number 3 of the Añute codex (Selden), which speaks of the mythical origin of the ruling dynasty of the Añute people, we see a ceremony where Lord 10 Eagle Reed through the priest 10 Flint, gives gifts to Lord 9 Rain to make an alliance. These gifts contain caged eagles and jaguars, as well as bags of tobacco and henbane, ritual objects, sacred bundles of the god “Ñuhu Dzavui” (Tlaloc), rope, axes and ritual arrows.

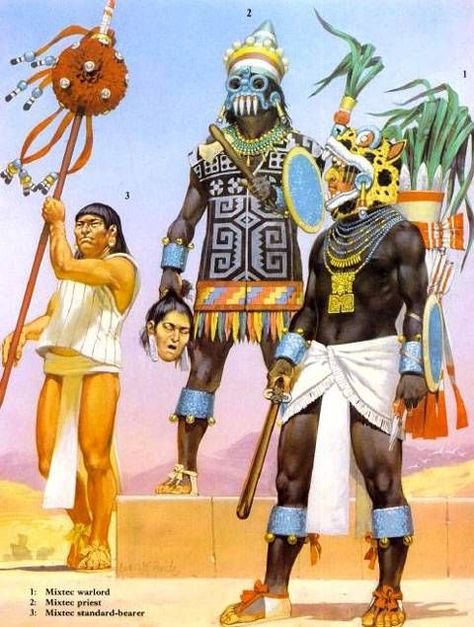

On the other hand, we see in the Tonindeye (Nuttal) codex, the elaborate feather art used: In the hands they carry fans with macaw and quetzal feathers, and various elements such as deer feet. In the headdresses worn on the head and hair, the use of macaw feathers with quetzal feathers and gold leaf.

“La Excan Tlahtoloyan contra Las Mixtecas”

Around the year 1440, the alliance formed by Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan began hostilities towards the Ñuu Dzavui/Mixtec kingdoms. After taking the city of Ndisi Nuu (Tlaxiaco, Oax.), the “Iya Coo Nduta” known in Nahuatl as King “Atonaltzin” of Yodzo Coo (Coixtlahuaca, Oax.), declared war on the alliance for control of trade routes. However, in 1464 the city of Yodzo Coo fell, and from then on they made war on more Mixtec kingdoms. As tribute they sent to Tenochtitlan every 80 days 400 huipiles, 400 loincloths, 400 tilmas, 20 gold jicaras, 800 quetzal feathers, elite warriors’ costumes, jade beads, 40 sacks of grana cochineal taken from places such as Tequevui (Tamazulapam) Yodzo Ca’i (Yanhuitan) Ñuu Ndeya (Mitlatongo) Yucu Ndaa (Teposcolula) Ñuu Ndaa (Tejupan), among others.

Colonial Period

During the XVI century, feather art was prohibited along with many other cultural expressions, however, it found shelter in the creation of sacred art called “Mosaicos de Plumas”, to elaborate feather images of virgins and saints. However, during the XVII century feather art disappeared due to the non-existence of aviaries, the death of the old “Tay Huisi Tnumi” (feather artists), and the preference for sacred art in oil and not made with feathers.

Huisi Tnumi/Mixtec Plumary Art today.

The art of feather art requires literally years of patient waiting and collecting feathers from different aviaries. Over time, it is a sort of trial and error to discover the mysteries of this pre-Hispanic craft. You should know that the feather work requires a large place, with little ventilation, well lit, work with clean hands, and to improve the results the feathers must be washed.

The secret is to do it with neutral PH shampoo, soaking them in a tub of water, rinsing them and drying them outdoors in a special box made to pass the wind, the sun, and the feathers are not blown away by the wind. This box is made with wooden slats and a plastic fabric called “mosquito netting”.

The feathers must be selected, and from this moment on you will work only with clean hands. The feathers are kept in open plastic bags inside cardboard boxes sealed with mothballs to prevent insects from eating the feathers, and the box should be placed in a cool, dry, high place so that they do not get damp and will keep for a long time.

After all that work, I make earrings, buckles, or cover surfaces with feathers and put them in my store to bring the Ñuu Dzavui/Mixteco Feather Art to the world!

This website will continue to grow and develop, it will not stay like this, meanwhile follow me on my social networks @Itandehui on FB and @Dzavuindanda_official on IG to learn more about feathers and feather art and above all, the Ñuu Dzavui culture, and the history of the Pueblo de la Lluvia.